“Douglas had been disarmed to an extent by his host’s unpretentiousness and received a political education of a kind,” wrote Yale historian David Blight, of that first meeting in his 2018 biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. That first encounter launched a complicated relationship that would last through the end of the war-and Lincoln’s assassination. Stearns, a leading recruiter of Black troops, that he admired Lincoln’s “decency and forthrightness” and that he left their meeting confident that “slavery would not survive the war and that the country would survive both slavery and the war.” While that was not the answer he sought, Douglass later told Major George L. The President, listening intently, explained that the conditions Black soldiers faced were a “necessary concession” for men of color to serve. On August 10, Douglass took his concerns directly to the White House-where, uninvited, he later wrote, he “elbowed” his way up the stairs “past all the angry white office seekers” waiting in line. READ MORE: Why Frederick Douglass Wanted Black Men to Fight in the Civil War The First Lincoln-Douglass Meeting “The slaughter of Blacks taken as captives,” wrote Douglass in his Douglass’ Monthly, “seems to affect him as little as the slaughter of beeves for the use of his army.” He focused his anger at President Abraham Lincoln.

He was also incensed by the Union government’s response to the Confederate treatment of Black prisoners of war, who were being tortured, killed and sometimes sold into slavery. Two of his sons had joined the 54th Massachusetts Black regiment.ĭouglass was concerned about the unequal pay of Black soldiers, who received $3 dollars less per month than white privates. In March, he had issued his famous “MEN OF COLOR to ARMS! broadside calling for Black men to enlist in the Union army. With the Civil War in full stride, Douglass was advocating for the equal treatment of Black Union soldiers.

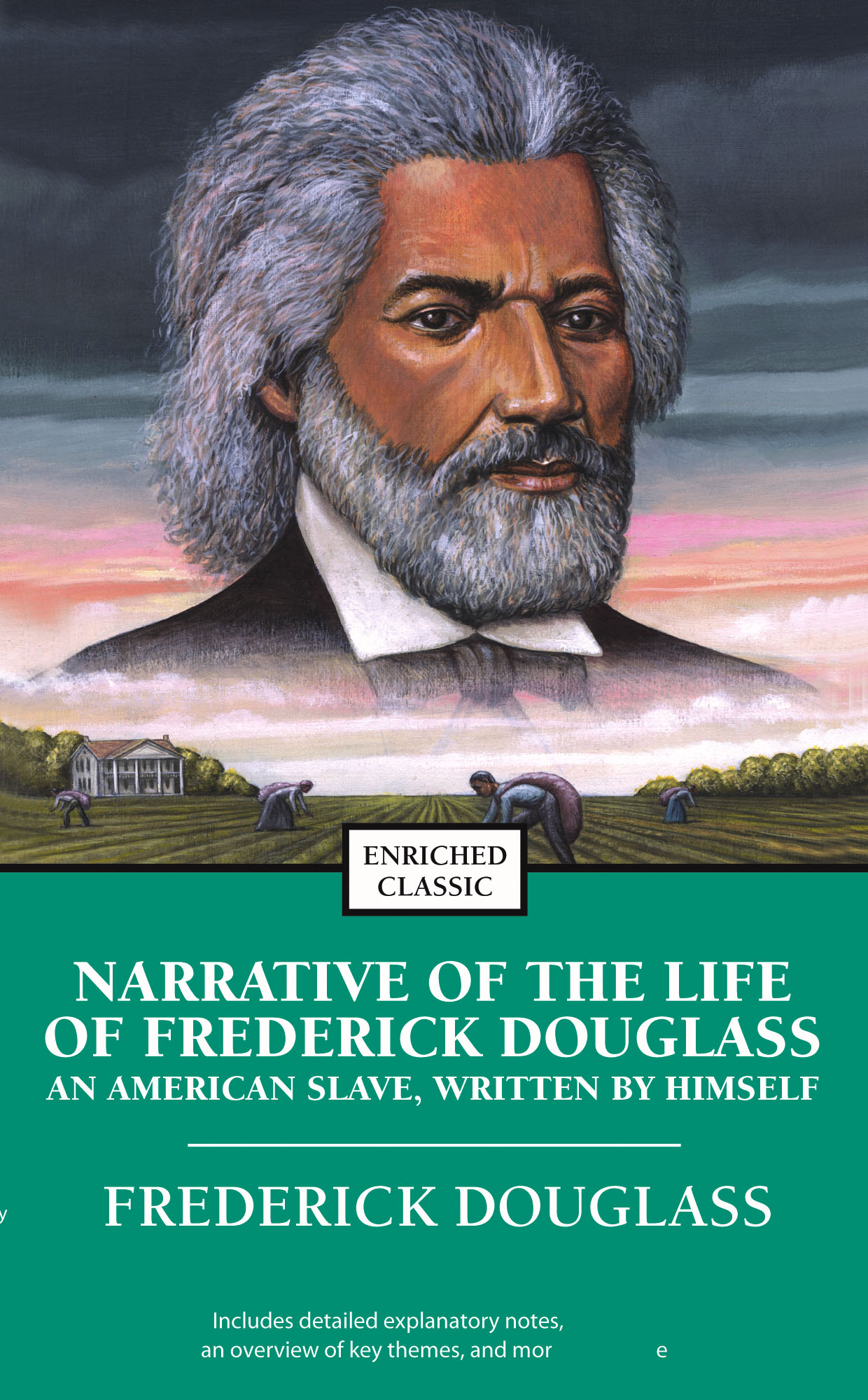

Since escaping from slavery to the North in 1838, he had written two bestselling autobiographies that recounted his journey from a Maryland plantation to lecture halls all over the world as a leading anti-slavery crusader, journal publisher and champion for African American rights. The first time they met, in August 1863, Douglass was perhaps the most famous Black man in the world. They met together three times in the White House, and while Douglass was at first harshly critical, he ultimately came to view Lincoln as "emphatically the Black man's president: the first to show any respect for their rights as men." In the middle of the 19th century, as the United States was ensnared in a bloody Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass stood as the two most influential figures in the national debate over slavery and the future of African Americans.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)